By Anjula Razdan

You don't need a Golden Ticket to visit Hershey's Chocolate World, but a Golden Map might come in handy. Although it's located in the small town of Hershey, Pennsylvania (the self-described "sweetest place on earth"), the ersatz chocolate factory is surrounded by a network of parking lots so byzantine you feel like you're headed toward the notoriously unapproachable Mall of America.

Fitting, since after you finally wend your way past the sea of cars and through the doors of Chocolate World, you're confronted by a dizzying array of products: pillows shaped like giant Hershey's Kisses, tubes of chocolate-scented lip gloss, trendy blue handbags embossed with miniature candy bars, and, of course, rack after rack of the Hershey chocolate candy most of us grew up with -- Hershey's bars, Kit Kats, Reese's Peanut Butter Cups, Almond Joys, you name it.

Founded on a humble six-acre plot in 1903 by Milton Hershey, the Hershey Company has since grown into a manufacturing juggernaut, single-handedly turning the town of Hershey into a major tourist destination that features not only Chocolate World but also Hershey Gardens, Hershey Theater, and Hersheypark, an amusement park that helps draws an astonishing 2 million visitors to town annually. Yet, taken as a whole, the various Hershey attractions are at once exhausting, lifeless, and obsolete. Sure, the town might service families who want to wear out their kids for the day, but the activities have little to do with any real passion for chocolate. To boot, the entire experience ignores -- and feels woefully out of step with -- the burgeoning artisanal chocolate movement.

We've come a long way from the time when Milton Hershey and Forrest Mars Sr. held us in thrall with their chocolate confections. To be sure, the Hershey Company and Mars Inc. together still dominate the $11.4 billion sales of the U.S. chocolate industry, but premium chocolate companies like Ghirardelli, Lindt, and Perugina, for example, have broken out of the specialty-store ghetto into mainstream venues. Americans, it seems, are finally getting savvy about chocolate.

"It's like olive oil," says Mort Rosenblum, author of the recent book Chocolate: A Bittersweet Saga of Dark and Light (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2005). "Once people catch on, it goes through levels. First is the big fad level where you can sell anything in a fancy box. Then, suddenly, people start noticing what's in the box, and you have to start producing good quality. We're at that stage now where a lot of people are demanding good chocolate."

After discovering the pleasures of premium coffee beans, heirloom tomatoes, and microbrewed beer, many Americans have learned to appreciate the difference between mass-produced, industrial chocolate like Hershey's (what Rosenblum refers to as "sugared wax") and artisanal varieties infused with ingredients, such as sea salt, balsamic vinegar, chili peppers, and saffron, that are normally reserved for savory dishes.

Of course, the spate of recent news reports touting the health benefits of dark chocolate have played a key role in our education. Turns out, wonderfully enough, that dark chocolate is good for you. Not only is it rich in minerals like iron, magnesium, and zinc, but it also contains the same all-powerful flavonoid antioxidants (which help prevent cancer, heart disease, and stroke) as red wine, green tea, and blueberries.

The key here is the amount of cacao, or cocoa, in the chocolate; essentially, the higher the percentage of cacao, the darker the chocolate and the richer the nutritional content. According to U.S. guidelines, anything labeled dark chocolate must contain a minimum of 35 percent cocoa solids (compared to only 10 percent for milk chocolate); most of the premium chocolates on store shelves go well beyond the government standards, typically ranging anywhere from 60 to 90 percent in cacao content.

Milk chocolate remains the most popular chocolate in the United States; last year, it brought in a staggering $3.6 billion compared with $294 million for dark chocolate (excluding Wal-Mart sales). But over the past several years the dark-chocolate market has grown at a steady clip, while sales of milk chocolate have stagnated, leading many industry insiders to predict that dark chocolate may well constitute the future of chocolate. A decade ago, only 20 percent of Americans said they preferred dark chocolate; today, that figure has grown to 35 percent. More and more people these days would probably agree with chef and food writer Jennifer Harvey Lang, who declared that "dark is to milk chocolate what Dom Pérignon is to Dr. Pepper."

No wonder, then, that the sleeping giants are starting to take notice. After all, the concept of healthy chocolate is a pretty powerful one, marketing-wise. Last summer, to the disappointment of food purists everywhere, the Hershey Company acquired Scharffen Berger, a Berkeley, California-based company that specializes in premium dark chocolates.

In September the company introduced Hershey's Extra Dark, a chocolate bar that contains an unprecedented (for Hershey, anyway) 60 percent cacao content and bears "The Antioxidant Seal," a stamp that displays an image of a cacao bean and announces the contents to be a natural source of antioxidants. What's more, Mars Inc., purveyor of M&M's and Snickers, recently created a new division called Mars Nutrition for Health & Well-Being and launched CocoaVia, a line of self-described heart-healthy snacks that boast a high antioxidant content.

Although market forces have nudged Big Chocolate on the road toward higher-end products, companies like Mars, Hershey, Cadbury Schweppes, and Nestle -- and, for that matter, the aforementioned premium companies, Ghirardelli, Lindt, and Perugina -- still haven't made a meaningful move toward fair-trade chocolate. Under fair trade, beleaguered cacao bean farmers, the vast majority of whom tend small family farms and cannot withstand mercurial global market forces, are guaranteed a stable, minimum price, not to mention fair labor and environmental standards.

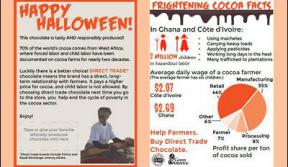

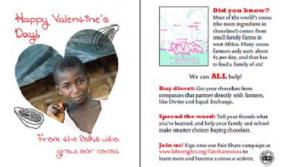

Some supporters say that fair labor might also help stamp out child slavery and child labor on cacao farms, especially those in Cote d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), a West African nation that produces more than a third of the world's cocoa, and where long-standing abuses include the purchase and enslavement of children as young as 9 years old to harvest the beans.

In 2001, soon after major news outlets first documented the reprehensible practice, most of the global chocolate companies pledged to uphold the Harkin-Engel Protocol, a voluntary measure that gave the companies until July 1, 2005, to develop a system that would certify cacao beans used in their various products to be free of slave labor. But that deadline came and went without much action, says Trina Tocco, a program assistant with the International Labor Rights Fund, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization.

"Like most voluntary corporate responsibility, time flew by and still there were barely even pilot projects set up in Cote d'Ivoire," says Tocco. Production timetables and quality standards are one thing, Tocco adds, but when it comes to child labor, the companies drag their feet.

On behalf of three young men from Mali who were allegedly trafficked and enslaved on a cocoa farm in the Ivory Coast, ILRF has brought suit against Nestle, Archer Daniels Midland Co., and Cargill Co. The advocacy organization has also filed suit against the U.S. government for failing to enforce the Tariff Act of 1930 (amended in 1997 and 2000), which prohibits the import of any products made with child labor.

What will happen is still up in the air, says Brian Campbell, an ILRF lawyer; however, it appears that the fight against child labor might be yet another casualty of the Bush administration's myopic Homeland Security agenda. During the course of the suit, says Campbell, "government lawyers stated to the court that Customs' priorities had changed post-9/11 to combating terrorism and that enforcing the ban on imports of goods produced by child labor is a low priority."

The U.S. government's reluctance to go after the chocolate companies is all the more reason, many say, to pursue fair-trade measures. After all, focusing only on the child labor issue does nothing to address the subsistence-level existence many cacao farmers eke out (most cacao farmers have never even tasted a chocolate bar). In fact, if farmers could secure a fair-trade minimum price, they might be less likely to turn to child labor, observes historian Lowell J. Satre in his new book, Chocolate on Trial: Slavery, Politics, and the Ethics of Business (Ohio State University Press, 2005).

"One of the reasons for the increased use of inexpensive child laborers in recent years has been the sharp drop in the price of cocoa beans," Satre writes. Lacking a steady income, cacao farmers will, many say, continue to use children to farm the notoriously labor-intensive crop.

On the other hand, fair-trade farmer cooperatives in Ghana, Indonesia, Brazil, and elsewhere have all sorts of ripple effects that build community, says Rodney North of the Bridgewater, Massachusetts-based Equal Exchange, the largest for-profit fair-trade company in the country and the first to sell fair-trade chocolate products.

"The gains from fair trade run the gamut from tangible investments in infrastructure to intangible improvements in organizational development and a community's sense of hope and confidence," North says. Farmers working with Equal Exchange distribute funds by democratic vote, including revenues to support communal projects; as often as not, higher earnings to offset low commodity prices are just as important. "Often what farmers need most is simply more income to pay for food, housing, clothing, medical care, school fees, and other essentials."

While demand for fair-trade chocolate has certainly grown in the past several years -- witness the overwhelming success of fair-trade and organic chocolate companies like Dagoba, Endangered Species Chocolate Co., Rapunzel, and Green & Black's, for example -- it still represents only 1 percent of the chocolate market. Worse, large fair-trade cooperatives like Kuapa Kokoo in Ghana sell only 3 percent of their stock at fair-trade prices because they can't find enough buyers.

The real challenge, say many advocates, is to get the big companies to buy into the fair-trade ideology. International human rights organization Global Exchange, for example, has launched a campaign to persuade Mars to buy at least 5 percent of its cacao beans from fair-trade-certified collectives.

"Larger companies might say they cannot find enough fair-trade cocoa for their needs, but that argument doesn't hold up to scrutiny," says Equal Exchange's North. Companies "have to at least buy what's already available on the fair-trade market before they try to cite supply constraints as an obstacle. Further, as any free-market businessperson or economist will tell you, if the demand exists, then the supply will grow to meet it. If more chocolate companies would start buying fair-trade cocoa, then the fair-trade farmer cooperatives could grow, too, for example by adding more farmer members from surrounding communities."

Of course, the quickest way to a corporation's heart is through its consumers. Perhaps the best way to inspire change is not through guilt (ˆ la novelist Barbara Kingsolver's famous declaration that a cup of coffee "doesn't taste so good when you think about what died going into it"), but simply to create a candy bar that tastes good.

"In the end, you can't tell people their mouth is wrong or stupid or unsophisticated," says Steve Almond, author of the recent book Candyfreak: A Journey Through the Chocolate Underbelly of America (Algonquin, 2004). "'Cuz people eat what they eat." Frederick Schilling, the 34-year-old founder of Ashland, Oregon-based Dagoba, which sells fair-trade and organic chocolate, agrees.

"I believe in fair trade, but the thing is, the chocolate has to taste good; otherwise people are not going to buy it," Schilling says. "So if you have high quality and fair trade, everyone wins: The consumers are happy, the farmers are happy, and the manufacturers are happy."

After all, who says we can't have our fair-trade, organic, chai-infused, dark chocolate truffles and eat them too?

Go For It

Want to help? Contact the major chocolate companies and ask them to buy fair-trade cacao.

Hershey Company

100 Crystal A Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; 800/468-1714

Mars Inc.

6885 Elm St., McLean, VA 22101; 800/627-7852

Nestle

Avenue Nestle 55, 1800 Vevey, Switzerland; +41 21 924 2111

Cadbury Schweppes

Box 12, Bournville Lane, Bournville, Birmingham 830 2LU, UK; +44 (0) 121 451 4444